🎉New- listen to the audio🎙️ version of this article🎉

While the weather is starting to cool, the discussion around Ethereum’s future has heated up. Solana’s breakout year and concerns over extractive L2s have shaken confidence in Ethereum. While prices and the market remain stagnated, progress has come on the research side. Below, Zhev looks at the MEV space from the perspective of order-flow auctions (OFAs), and evaluates what could well be the final MEV boss: running credible auctions on censorship-resistant blockchains.

Collectively, we’ve progressed rapidly towards the MEV-mitigating goals set out by Flashbots and co-opted by Ethereum. In fact, the success of Flashbots – practically the face of MEV on Ethereum – implies that the illumination of the dark forest goal has almost been met. The other two – democratization of mindful extraction, and the distribution of benefits – are also seeing more daylight. However, there remains more work to be done before Ethereum reaches the MEV utopia, where leakage is minimized at every stack of the protocol.

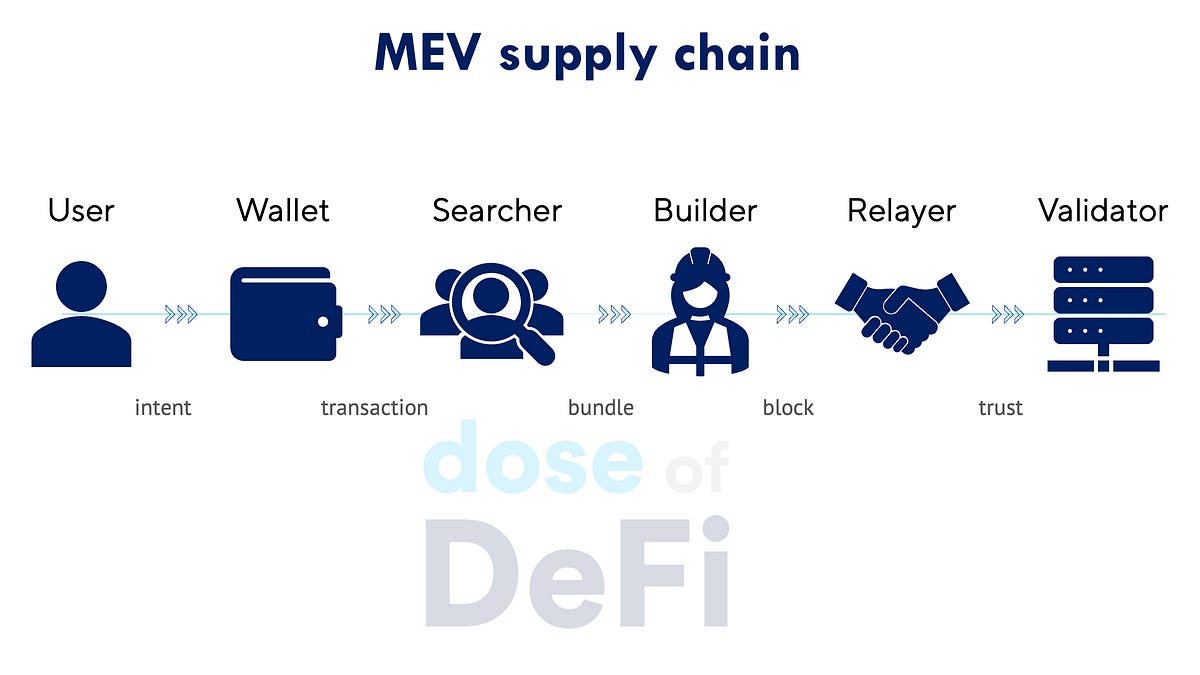

The easiest gotcha for MEV on Ethereum is that most auctions are entirely offchain and centralized. This means that the protocol cannot give any guarantees regarding execution to any participant in such auctions. Rather, guarantees are bestowed by a second agent who is more privileged in the mechanism.

This is most clearly illustrated with Order Flow Auctions (OFAs). Such auctions were supposed to be a solution to the problem of value distribution, a way for users to recapture the value they’re responsible for creating by running an auction antiparallel to MEV-Boost, or any such similar PBS auctions. And while OFAs have enhanced user welfare, there are other issues. OFAs rely on trusted intermediaries who are ultimately at the behest of the oligopolistic builder market, which has proven willing to censor transactions as they please. As such, efforts must be made to ensure that block producers aren’t able to influence applications’ transactions and alter them in their own favor.

This ultimately means that new OFA designs that are decentralized are needed. And more importantly, so is credible infrastructure with censorship resistance to run these OFAs, be it SUAVE and FOCIL or the newly introduced BRAID – which would introduce multiple proposers to the Ethereum protocol. Although SUAVE and a Flashbots/Ethereum-aligned future seemed like the inevitable MEV endgame, the route that brings multiple proposers to Ethereum looks like the unexpected favorite.

In a previous article, we evaluated some of the emergent OFA platforms at the time, which serve as trusted intermediaries between extractors (searchers and builders) and users under the PBS framework.

Before we move on, it’s important to note that most performant OFAs to date – such as UniswapX, CoWswap, and the like – are application-specific (in this case, they offer OFAs for trade/swap execution). This means they are not generalizable MEV infrastructure but specifically designed to prevent frontrunning retail traders, so while valuable, it’s not a long-term building block that offers the programmability of say a smart contract. This also doesn’t even factor in other pain points such as the cost of bootstrapping a solver network that actually prioritizes user welfare (promise you won’t front run anyone, bro), and the disadvantages that come with a siloed solver network.

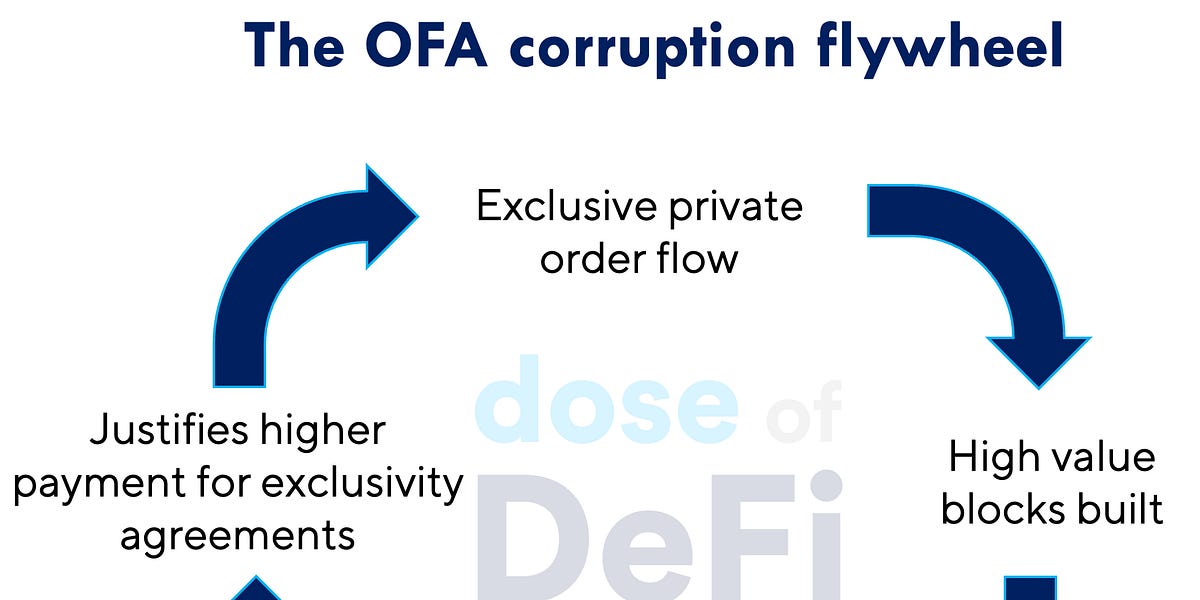

There’s also the problem that most OFA platforms thrive on a payment for order flow (PFOF) or exclusive order flow (EOF) model. Here, user-facing applications such as RPCs, wallet providers, and decentralized applications receive payments from extractors for exclusive access to the users’ orders, a sort of vertical integration.

So then, we have two key problems:

-

the proliferation of backroom deals and a PFOF model that isn’t optimal for user welfare.

-

block producers (builders and proposers) can censor transactions which pay them only a minimal portion of the transaction’s extractable value. In other words, the base protocol’s low cost of censorship.

To overcome the first problem, application-agnostic/generalized OFAs are being designed with the goal of being implemented as a portion of the protocol’s execution logic (just like MEV auctions), so that applications can easily implement OFAs with lower overheads. This would ultimately redefine how user welfare overlaps with inclusion/execution guarantees.

The overarching disadvantage of conducting offchain auctions is that the disincentive for predatory behavior isn’t native to the system, but rather enforced through loss to reputation and/or fixed penalties applied by a (centralized) authority.

Also, besides other factors (such as participation costs) which invariably lead to an undesirable oligopolistic extractor regime in MEV markets, the PFOF model is unavoidably oligopolistic, as demonstrated by the increasing oligopoly of market making in TradFi by HFT firms.

This oligopoly isn’t achieved through fair competition among extractors, where they optimise for features and user welfare. Rather, via backroom deals which the user doesn’t necessarily benefit from, and might not even be aware of. In fact, 80% of block builder revenue comes from private order flow – so why take away the punch?

In order to stop this feedback loop, work must be done to introduce more competition and decentralization in both the OFA market and in the block builder market.

The most important thing to fix is the centralized builder market, which prevents MEV auctions from being run onchain. We’ll discuss that in more detail below, but wanted to highlight two promising OFA designs, MEV-Share and Atlas, which make improvements on two key areas: privacy and application sovereignty.

The primary design difference between MEV-Share and Atlas lies in where the auction’s inclusion guarantees flow from. The former relies on guarantees from block builders to be credible, so decentralization and competitiveness of the builder set is very important, which Flashbots says is why they’re building SUAVE.

Meanwhile, Atlas chooses to use an Entrypoint contract, akin to ERC 4337, to get direct access to an alternate mempool (called ‘ops relay’) hosted by an interested party. This difference in the source of the inclusion guarantee allows Atlas to be much more flexible, as it doesn’t need a PBS-supportive protocol to be performant. However, this comes at the cost of its gas efficiency since there’s a lot of verification to be done onchain.

These designs improve user welfare, but ultimately, they will only work if there is credibly neutral infrastructure to run these auctions.

In “credible, optimal auctions via blockchains” Tarun et al. examine the effects of blockchains and cryptography on credible auctions. The notion of credibility in this context is based on Akbapour’s work where a credible auction is defined as one in which the auctioneer’s (seller’s) revenue is better off when they follow the described mechanism. The results from Tarun et al. show that censorship-resistant blockchains fuel credibility.

The question is can a blockchain run a fair, high-value auction while maintaining censorship resistance? In the current setup, Titan, rsync and beaverbuild (the three largest block builders on Ethereum) have a privileged position for any onchain auction and will simply censor any transaction from an auction that tries to redistribute MEV they have dutifully earned. This is a huge obstacle to efforts to reduce LVR and the CEX-DEX arbitrage. Thus, any credible OFA would only become fully performant when there are guarantees of fair inclusion and censorship resistance against all odds from the blockchain.

The prevalent questions, then, are (a) how can Ethereum (or another blockchain) provide these guarantees? and (b) in what ways can the power of a block producer be limited to ensure there is no ability to censor?

There are two paths emerging for where the market will go. The first is a continuation of the MEV mitigation and redistribution strategy of the last four years, which has been led by Flashbots. And the second path tries to fix the source of MEV privilege by removing the proposer monopoly entirely.

Flashbots launched with a charge to “frontrun the MEV crisis”. This was a tacit acknowledgement that they weren’t going to fix the crisis, but rather build extractive tools and then figure out how to make them fair.

SUAVE (or the Single Unifying Auction for Value Expression) is the endgame for this vision, a blockchain that is a decentralized block builder for any EVM chain.

SUAVE extends MEV-Share’s programmable privacy to execution environments which can use it as a decentralized block builder, or even a shared sequencer. It utilizes “TEE-kettles”as confidential compute enclaves, and runs as “SUAVE chain” powered by Clique’s proof-of-authority consensus protocol. SUAVE intends to be the credible infrastructure for MEV auctions, essentially becoming the home of all MEV extraction, but with the upside that it’s being run on a decentralized blockchain, rather than the opaque MEV supply chain of today.

This approach offloads the problem of censorship resistance to a different environment than the L1, which means Ethereum’s censorship-resistance would be dependent on another chain.

To shore up its censorship-resistance, Ethereum researchers have proposed inclusion lists. While the specifications differ between designs, the basic premise of inclusion lists is to allow the proposer to forcefully include some transactions in their slot (or a future one!), potentially against the wishes of a censoring builder.

FOCIL takes this a step further to move the production of an inclusion list from the slot’s proposer, to a leaderless committee of validators selected randomly. For every slot, a random set of validators produce a local inclusion list from transactions in the mempool, which must be included in the next block.

This design is more of a patch over one of the many leaks of PBS on Ethereum, and the thing with patches is that they mostly don’t last. The team at init4 tech also recently showed that forced inclusion doesn’t prevent censorship of most DeFi transactions. FOCIL may be useful but it will not address the builder monopoly.

So path one is where Ethereum implements something like FOCIL at the protocol level and then relies on SUAVE to decentralize its block building market.

Flashbots and the Ethereum Foundation have both agreed to work to externalize MEV auctions outside of Ethereum, but that conventional wisdom is beginning to fray with the emergence of multiple-concurrent proposer (MCP) designs and BRAID.

With multiple proposers, rather than having a single proposer append blocks for every slot, the protocol implements a leaderless scheme in which at least two proposers are responsible for producing the payload to be executed for the slot. This removes the monopoly a single entity has on inclusion and allows the protocol to expose a more expensive cost of censorship at every slot, more than it would have in a leader-based scheme. This is due to the observation that a single slot with K proposers achieves the same cost of censorship that would require K slots on a single proposer chain.

The work of Max Resnick on BRAID has again sparked interest in the topic as a viable means for increasing the censorship resistance/cost of censorship of a protocol. While the specifications are still being fleshed out in real time, BRAID and its multiple-proposer architecture is a wrecking ball to the current Ethereum roadmap and its PBS architecture (it’s seen as a direct alternative to FOCIL). After being presented last month, BRAID quickly gained support from Dan Robinson of Paradigm, which is notable given their investment in Flashbots, and SUAVE by extension. Not everyone from Paradigm is on board however, and it looks like SUAVE will compete with BRAID for what will ultimately be the long-term solution for MEV mitigation. Max was even on Bankless twice in six weeks trying to shift the Ethereum mindshare (and it appears to be working – at least on the “Are L2s extracting?” discussion).

There’s also been other criticism of BRAID, which is aimed at its idea of a leaderless scheme for consensus. In such a system, there has to be some allowance for latency, so that proposers can achieve some extent of simultaneous release. A short duration would lead to missed slots and potential liveness failures. But longer ones would expose the last-look problem, where agents can delay in order to view the blocks released by other proposers and potentially grief them.

If implemented, BRAID would upend the MEV supply chain. There would still be leakage but no longer a clear actor in the system who could exploit it. This would mean more redistribution based on competitive dynamics rather than goodwill.

MEV has proven such a vexing (and interesting!) problem to solve, we often forget why it’s so damaging to user welfare in the first place. Users now fear transacting onchain because of the predatory behavior of MEV. Indeed, if you have to trust someone, why not opt for CEXes? They’re more friendly than the creatures of the dark forest. That sentiment will not change overnight, but the work being done now gives application developers the tools and infrastructure to make MEV invisible without new centralization risks.

This would be a huge step forward, but would it ultimately fix the problem of private order flow?

Probably not. But it will fix exclusive order flow where entrenched builders purchase flow and further cement their builder monopoly. Instead, without a centralized builder market, the problem of private order flow becomes a question of best execution for application developers.

With credible infrastructure to run auctions that cannot be censored by block builders, applications and other transaction originators will be more in control of their MEV supply chain. This means they’ll have to become more adept at bundling transactions or outsourcing to third party builders who do. The role of tightly packing blocks will still be needed but done by distinct actors at different parts of the supply chain.

-

USDS and SKY launch on Ethereum, completing MakerDAO rebrand Link

-

Centrifuge launches new institutional RWA Morpho market on Base Link

-

Visa releases new dashboard on stablecoin usage Link

-

House lawmakers clash at DeFi’s first congressional hearing Link

-

Coinbase’s cbBTC reaches $120m one week after launch Link

-

SAFE proposes native swap fee Link

-

Doppler, a liquidity-bootstrapping hook design on top of Uniswap v4 Link

-

Atlas, a high-performant DeFi Ethereum L2 based on SVM, launches testnet Link

-

ZKsync announces onchain governance system Link

That’s it! Feedback appreciated. Just hit reply. Great to be back after a restful summer!

Dose of DeFi is written by Chris Powers, with help from Denis Suslov, Zhev and Financial Content Lab.