The vibes are weird out there. Meme coins may have finally overstayed their welcome, but there’s still lingering fears that nihilism has infected the true believers. Now, this Bybit hack? Fret not. We’re still here, writing and talking about new financial markets for a freer and more sovereign world. Zhev continues this journey below, with a review of the top DEX players, and their plans to usurp TradFi. Onward.

– Chris

ps – in Denver next week!

While the prospect is unsavory for DeFi purists, there’s now little doubt that crypto’s greatest product – apart from stablecoins – is permissionless tokenization (and the trading of such tokens). Best case, these tokens can be considered analogous to company stocks, granting users governance rights to pilot associated products towards optimality. As it currently stands, they’re simply a means to convert attention into monetary gains.

Over the years, we’ve seen the evolution of various models of decentralized exchanges (DEXs) that seek to facilitate the trading of tokens. The distributed nature of blockchains reduces their ability to support conventional limit order books, as is common in centralized exchanges. This is why the AMM model is more commonly adopted for onchain trading. As blockchains have scaled and trading automated, we’ve seen a convergence between order books and AMMs to the point that they’re now (almost) indistinguishable.

Much has been learned since the days of 0x and Bancor. The speculation and frenzy of DeFi, NFTs, and memecoins has spurred newer and better exchange designs that are close to an optimum state of usability. At the core, these designs are all focused on minimizing and democratizing MEV.

Below, we zone-in on the onchain market-models development trend by examining top players in derivatives and spot trading. Specifically: Drift, Jupiter, dYdX, Hyperliquid, and Uniswap.

Based on our analysis, it seems we’re close to the end state for market design. And that the winner of this round in DeFi will be the one who knocks off TradFi.

Before we get into the review and analysis, a quick recap on general properties and considerations when building exchanges as they relate to underlying blockchains.

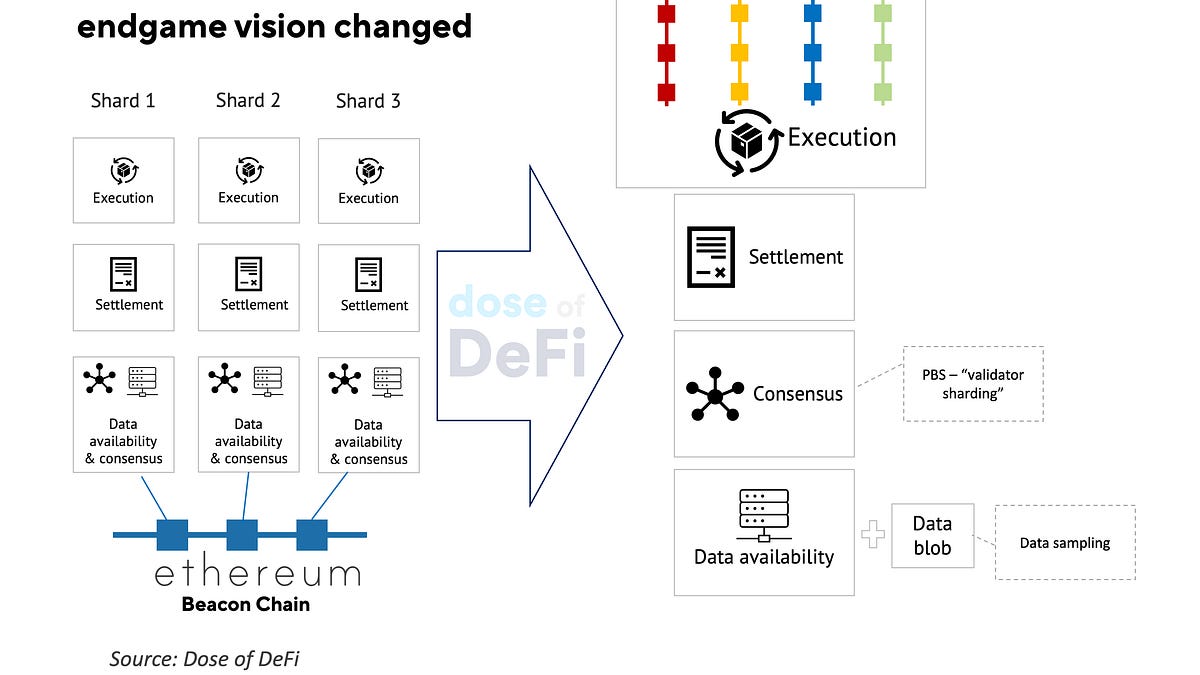

The initial model for blockchains was a single data layer, which all sorts of activities can be coordinated and recorded on, evident in Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Solana’s design. We refer to this model as ‘general purpose chains’, i.e., chains that aren’t built to cater to any specific application category, but rather to support as many as possible.

Generally, this model faces a trilemma of tradeoffs between security, decentralization, and throughput: optimizing for any two of these goals lessens the chain’s chances of achieving the third. It’s a subjective belief for spectrum-based metrics – but a widely acknowledged one – that Ethereum has prioritized security and decentralization at the cost of throughput. This is similar to Bitcoin, which is even less decentralized these days, but in contrast to Solana, which pursues security and throughput with less focus on decentralization.

So while applications can launch on Ethereum to access better security and censorship-resistance guarantees, Solana is arguably a better chain for latency-sensitive applications such as limit order book markets.

Nevertheless, it’s not news that general purpose chains are inherently limited in the amount of throughput they can offer applications building atop them. Even more so if they wish to maintain a credible level of decentralization/distribution. Furthermore, most applications may wish to retain their value rather than leaking it to the underlying chain through MEV. These are the driving ideas of the appchain approach.

All application-specific chains (or simply, appchains) have to make design choices concerning their consensus network/mechanism, preferred virtual machine, whether to be an L1 or L2, and other optimizations. L1 appchains have the benefit of ground-up building that enables them to make improvements by customizing components, while L2 appchains are easily composable with their L1s – and potentially other L2s – making it easier to attract liquidity.

All these factors must be considered, especially for onchain exchanges, as the slightest misconfiguration in setup could lead to an incorrect liquidation, a bad order match, or any other myriad of faults that would scare away user liquidity. Perhaps unsurprisingly, most teams prefer the L1 appchain setup for customization benefits and deal with liquidity attraction as a secondary issue, rather than risk reliance on an external avenue.

The table below summarises the key characteristics across the three main approaches to choosing a chain for an application.

It’s now time to go over the architecture of the five aforementioned dominant DEXs. Given the considerations each will have had to make around design (as highlighted above) we present these DEXs categorised under each of the three main approaches.

Drift

The Drift protocol is built atop Solana, allowing it to comfortably serve limit-order-book-based exchanges within certain bounds. It is an onchain decentralized exchange that settles user trades via three routes:

-

Just-in-time (JIT) liquidity auctions: Orders are submitted to a committee of market makers who compete to satisfy the order at the best possible price within a specified window.

-

Limit order book: Users specify their preferred order settlement prices during submission to a network of ‘keeper bots’. These bots each maintain an offchain index of submitted orders, which they can either:

-

sort and match by price-time priority to other limit orders

-

use to fill a JIT liquidity auction, or

-

settle via the virtual AMM’s reserves.

-

-

Virtual automated market maker (vAMM): A last-resort liquidity source for the guaranteed settlement of user trades.

Jupiter

While Jupiter is mostly used as an aggregator, it has also developed a derivatives market, offering users up to 100x leverage on a limited number of assets. Jupiter’s aggregator product enables it to have better flow and deeper liquidity reserves, which ultimately imply better order settlement prices for users.

The derivatives exchange is supported by the Jupiter Liquidity Provider pool (JLP) which acts similarly to an AMM pool to accept user assets as a liquidity backstop for orders, however the users’ orders are for derivatives, rather than spot positions.

Processing of orders occurs in a two-step process:

-

The user submits a “request” transaction of their order to the chain via the application’s front end.

-

A keeper monitors the request transaction onchain and executes it using liquidity from the JLP pool.

The performant L1 approach for DEXs rests on the condition that the revenue of privileged agents (e.g. block builders, validators, proposers etc.) in the default mechanism is greater than the revenue they’d get from malicious actions such as sandwiching. Various L1s have adopted extraneous guardrails for these problems: Flashbots for Ethereum, Jito for Solana, and Skip for Cosmos. However, speedy order processing with adequate censorship-resistance is still not in sight.

In the case of Drift/Jupiter and Solana, the underlying L1’s stated goal is to serve as a decentralized NASDAQ, or more recently to “increase bandwidth, reduce latency”. This means pursuing throughput and security at the expense of decentralization. As Solana’s throughput increases, the hardware requirements for validators do as well, causing more validators to fall behind or shut down operations entirely.

This leaves the network in the hands of only a few validators who will inevitably begin exploring other avenues for revenue aside from the foundation’s subsidy. This also means applications atop (such as Drift) will begin to leak value to such ‘unaligned’ validators, leaving users worse off due to MEV.

Nevertheless, the search for the perfect L1/L2 continues with the likes of Movement, MegaETH, Monad, and Atlas scheduled to enter the frame very soon.

dYdX v4

dYdX was one of the first providers of onchain derivatives. The dYdX Team has since pivoted from an Ethereum Layer 2 chain offering, to building a standalone L1 within the Cosmos hub. V4 was launched as a CosmosBFT-based L1, to enable the protocol to take advantage of the mechanism’s relatively unopinionated design specifications and customize validators’ duties to increase throughput.

The dYdX chain is populated by validator nodes (which are responsible for gossiping/executing orders and finalizing blocks) and full nodes (which pass real-time data to indexers). Therefore, the chain’s p2p network is responsible for:

-

Executing received orders by matching them to each other.

-

Including matched orders in blocks and extending the chain.

-

Providing the data related to order execution to users.

Part c. is carried out collaboratively with indexers, which are read-only data endpoints optimized to serve users similarly to RPCs in Ethereum. Indexers ingest data streams from full nodes and decompose them into either onchain or offchain categories, before serving them to users or anyone else.

Having a p2p network with customizable functions enables the dYdX chain to implement a novel MEV mitigation scheme through ‘vote extensions’. Its strategy is two-fold as it:

-

Eliminates the block proposer’s first-look privilege by enabling collaborative block building with other validator nodes, effectively simulating a leaderless mechanism (although execution is still entirely the proposer’s duty).

-

Implements a frequent batch auction (FBA) in each block for similarly priced orders, so that ordering advantages are minimized.

Hyperliquid

Another example of the appchain approach, Hyperliquid has gained impressive traction within barely two years of launch. This was initially due to its smooth UX relative to competitors, with users hailing it as an onchain, no-KYC centralized exchange. Then came its HYPE token, which has become the new standard for fair product token launches.

The Hyperliquid L1 is a PoS chain that runs on a variant of the HotStuff consensus mechanism referred to as HyperBFT. This mechanism is optimized to enable validators to run a low latency order book that serves users at a self-reported average rate of 100k orders per second.

So far, it seems the L1 appchain approach hasn’t lived up to the associated hype due to the unique issues both dYdX and Hyperliquid face. On one hand, dYdX remained steadfast to the open-source/decentralized ethos of crypto to build an L1 that is sufficiently censorship-resistance for its purposes. However, it has been criticized for its weaker performance that has caused it to lose a great portion of market share. Its token distribution model is also being called under question as the underlying cause of its continued underperformance, especially since it could easily be viewed as extractive and unfriendly to retail investors (relative to Hyperliquid’s friendly airdrop and distribution model).

On the other side, Hyperliquid has gone its own route with mostly closed-source developments and a centralized model. Critics say its rapid rise to success is due to a great deal of centralization that persists at almost every level of the application. Its proponents tend to disagree, especially given its continued outperformance on almost every metric. However, these two arguments don’t overlap; if anything, Hyperliquid’s continued success points to the risk profile of its users. We believe it’s a good product, just not a DeFi product. Yet.

While we present Unichain as an example under the L2 appchain approach, it’s worth noting that the developing team (Uniswap) is perhaps better classified as a ‘composable stack’. This is because their products span virtually every area, from wallets to various DEX models, and now a DeFi appchain.

Uniswap started its journey as a permissionless AMM with asset prices defined by their quantities in a pool. Over the years, the initial model has been altered to meet the demands of an ever-evolving user base, as summarized in the table below:

The latest iteration comes with a great deal of improvements, the most notable being hooks and the singleton architecture:

-

Hooks are subsidiary contracts that can be called at a specific point during a user’s interaction with a liquidity pool, in order to trigger a pre-designated action.

-

The singleton architecture is an optimization for saving gas, but it also enables what is referred to as ‘flash accounting’. This system enables Uniswap v4 to transfer assets only on net balances, so that swaps involving multiple liquidity pools will require less onchain storage updates and consequently be more efficient.

Together these features shift Uniswap v4 towards the modular design principle for lending markets we discussed previously. As such, it’s no longer a simple product but a platform, to which complexity can be safely introduced by developers without loss of composability.

Aside from its primary product, the Uniswap team has also created an RFQ market, UniswapX. This is essentially an intent-powered market wherein users can define their preferred execution conditions for a trade, while fillers compete in an auction to satisfy user preferences.

While seemingly different, both Uniswap v4 and UniswapX are actually complementary, as has been laid out by the team. The introduction of hooks and arbitrary fee values in Uniswap v4 leads to greater liquidity fragmentation across unique pools, leading to higher routing complexity that translates to higher transaction fees for the user. While the Uniswap auto-router is optimized to solve this problem, there is no guarantee that its selected route for a user’s transaction is the most optimal; thus users pay more with no guaranteed outcomes.

This problem is being addressed by UniswapX, which allows users to set tight bounds on their expectations while offsetting execution to experienced fillers, who have access to more information and inventory, and compete to satisfy users for a fee. Cowswap is coming at this from the other direction, starting first with an intents-based aggregator and then designing a MEV-capturing AMM.

The Uniswap team has also announced they are building out a new rollup tailored for DeFi applications called Unichain. While this came as a surprise to some, it makes sense that one of the biggest drivers of order flow would want to control it better, especially since better flow control implies better MEV mitigation (among other things).

Moreso, the remodeling of Uniswap v4 as a baseplate will inevitably drive the need for a more performant base layer, one which can easily support hooks’ features, especially the necessary throughput. For example, in the case of the speed necessary for onchain limit orders. Uniswap v3 already had the simplest form of limit order books with its ticks, so v4’s hooks will inevitably perfect this, and then require more infrastructure support.

Unichain can easily satisfy hooks’ latency demands with its ‘flashblocks’ (essentially glorified pre-confirmations), while reducing the toxic flow users are exposed to due to ordering via its sequencer-builder separation model.

While these DEX projects are all competing with each other, they’re really after CEXs and King Binance, where most derivative and spot trading takes place. It’s telling that there hasn’t been a new successful upstart CEX this cycle. There’s no FTX trying to challenge Binance. In fact, it’s Hyperliquid that has finally eaten into Binance’s overwhelming lead. And the latter certainly feels threatened, making (in)direct shots at Hyperliquid on X.

Hyperliquid feels very much of the moment. It is rightly criticized for its extremely centralized model, but if we take a step back, we can see that it represents an evolution of new exchanges launching with more and more crypto-native financial infrastructure first. Coinbase was a CEX, but then Binance launched with a token from the start. Now Coinbase has its own L2 and while Binance.com is dominant, BSC is arguably one of the big three smart contract blockchains, along with Solana and Ethereum.

In fact, all new innovation in crypto exchanges these days is coming from DEXs and in DeFi. CEXs gave us the perpetual derivative – a genuine financial innovation – but DEXs are quicker to list tokens, unlock new yield opportunities, new pooled lending, and most importantly, are driving the RWA push. Coinbase and Binance are not trying to innovate TradFi with their CEXes. They’ve bet on Base and BSC to do that.

The key question is whether the DEX that slays TradFi will be one that specializes in strong distribution and on & offramps, like Binance, Coinbase or Hyperliquid, or from one where the tech shines first (be it an L1/2 app chain or high-performant general purpose chain). Our bet is on the infrastructure wagging the distribution, eventually.

-

North Korea hacks Bybit for $1.5bn Link

-

Coinbase says SEC has agreed to drop enforcement case Link

-

Hummingbot releases v2.3 Link

-

Vitalik proposes higher gas limits for Ethereum L1 Link

-

Berachain: A story told through charts Link

-

Ethereum Foundation deploys 45,000 ETH into DeFi Link

-

Overview of new regulatory efforts in US congress Link